Led by Arsène Wenger, Chief of FIFA’s Global Football Development Division, the members of the TSG analyse the game as coaches, focusing on the key technical aspects. At the same time, FIFA’s Football Performance Insights team generates and decodes the data collected by its extensive team of analysts. During and after each tournament, all this information is verified and collated by FIFA’s experts to build up a detailed picture of what is happening throughout the elite football pyramid.

When compared to similar data from previous tournaments, this information gives us valuable insights as to how the modern game is changing and evolving. The metrics provide points of reference from which we can benchmark performance, the specific strengths of successful teams, player development pathways, coach education and talent development programmes for all 211 member associations.

This article explores some of the overall numbers that emerged from FIFA Women’s World Cup Australia and New Zealand 2023™ before examining some of the key trends in further detail.

Increased competitiveness

Despite the expansion of the finals tournament from 24 to 32 teams in 2023, this was a more competitive FIFA Women’s World Cup than in 2019 or 2015. As the TSG’s Chan Yuen Ting observed, this was primarily due to a marked improvement in the overall standard of play:

“It was really interesting”, she said. “Before this World Cup there were concerns that there would be big scorelines, but it didn’t happen. The tournament debutants were very competitive, extremely well organised and had solid structures. Teams were very difficult to break down and the defensive strategies of teams really improved. The standard of goalkeeping improved, attacking teams had less time and space to get attempts at goal, and the game management was better.”

Her view is borne out by a range of statistics. For instance, even allowing for the 12 additional matches played in expanded 2023 tournament, an analysis of the normalised data shows the number of goals per game reduced by 9% in 2023, averaging 2.56 compared to 2.81 in both previous competitions.

As Chan noted, eight teams were making their tournament debuts, and there were some concerns about how they would fare against nations that had more World Cup experience. However, FIFA’s decision to expand the tournament as part of its commitment to developing women’s football was vindicated by a very competitive group stage that saw the average goals per game reduced to 2.65, down 12% on 2015. The number of clean sheets also increased by 14% compared to 2015, and there were some very impressive whole-team defensive performances. There were ten 0-0 draws (including games that finished 0-0 after extra time) in 2023 compared to just four in 2015 and 2019 combined.

Improvements in the standard of goalkeeping also helped to keep games competitive, as former Germany goalkeeper Nadine Angerer points out:

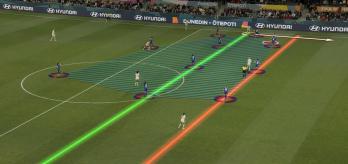

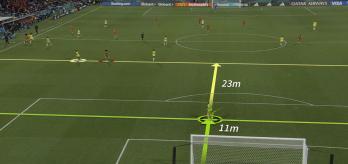

“The goalkeepers really surprised me; there was such a big difference from previous tournaments. Their offensive involvement when their teams had the ball was excellent, as they were confident and composed with the ball at their feet and in their distribution. They had such variety in their passing and were able to do it under pressure. We also saw high levels of game awareness and the vision to see space. When their teams did not have the ball, they protected the space behind the defensive lines, allowing their defences to play higher. They were much more involved in the game [than they have been in the past], and were stronger and more confident in the air. We also saw some very big saves. It was impressive.”

A shifting age profile

The women’s game is growing and developing exponentially. As more clubs become fully professional and set up full-time academies, we are seeing young players progress to the senior game earlier in their careers. Interestingly, 42% of players under the age of 21 at this tournament were representing countries appearing at their first World Cups, with Haiti (10), Panama (5) and Zambia (also 5) boasting the highest number of players under 21 in their squads.

Colombia winger Linda Caicedo (18) and Spain forward Salma Paralluelo (19) were among the standout young talents in this competition. Both players also starred for their countries in the 2022 U-20 Women’s World Cup in Costa Rica and have also represented their respective national sides at U-17 level. Indeed, Caicedo played in the U-17 World Cup, the U-20 World Cup and the senior World Cup in the space of just eleven months.

Gemma Grainger, who was recently appointed Head Coach of Norway’s national women’s side, was particularly struck by the number of players under the age of 21 progressing into the senior ranks.

“It's a sign of the continued investment in youth level and the exposure these players are getting to play with, and against, higher quality players in tournaments and at their clubs. Countries have been identifying their high-potential players earlier and are working out ways to enhance their development. These young players are so technical, physical and game-aware and have no issues playing in front of large crowds,” she explained.

When we extend the age-profile to consider players both under 25 and over 25, and compare the distribution to 2019, we get an interesting insight into how the senior squads of different countries have developed over the four-year cycle. For instance, England, who finished runners-up in 2023, showed the biggest shift in their squad’s age profile from 2019, with seven more players under the age of 25 than there were four years previously. The Norwegian and Canadian squads also showed major shifts in the other direction; both had six more players over 25 than in 2019.

Squad management and use of substitutions

In 2023, for the first time at a FIFA Women’s World Cup, teams were allowed to make five substitutions in the game (not including concussion substitutes). This increased the opportunity for in-game changes, and led to high numbers of outfield players getting game time during the competition.

For Chan, the ability to make five substitutions had a significant effect on events on the pitch:

“The possibility of making five changes gives more choice to the head coach and more options,” she said. “It enables the coach to make tactical changes earlier and bring in players that can really change things. Often in previous World Cups, substitutions were like-for-like, but now the coach can really alter the game tactically. The extra changes mean teams can sustain high levels of performance and the speed of the game does not diminish in the latter stages. It also means more players get playing time and this is great for their development.”

Again, this observation is backed up by statistics. Of the 32 teams competing Down Under, seven of them (France, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, China, Japan, Netherlands and Norway) used all of their outfield players during the tournament, while no team used fewer than 17 players. However, there is no direct correlation between the number of players used and progression in the competition. To prove the point, winners Spain used 22 players in total (including all of their outfield players), while runners-up England used just 17 players.

When compared to 2019 (when each team was permitted just three substitutions each), more substitutes were used in 2023, but teams tended not to use the full quota of five each (i.e., a maximum of ten in total per match). In 2019, an average of 5.6 substitutions were made per game, while in 2023 the average was 7.4 per match.

Interestingly, Spain used their full quota of five substitutes in five of their seven games on route to the title, perhaps indicating the exceptional depth of their squad.

Summary

Despite expanding from 24 to 32 teams, FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023 was a more competitive tournament than in 2019 or 2015. This is evidenced by the fact that there were fewer goals scored per game and more clean sheets than in the previous two competitions, suggesting that the gap between the top teams and the rest has narrowed.

Another notable aspect of this tournament was that so many young players were clearly ready to compete at senior level very early in their careers. The expansion of the finals tournament 24 sides to 32 gave more teams exposure to playing in a World Cup. The continued professionalisation of the women’s game and of full-time club academies are contributing factors to this development.

Increasing the maximum permitted number of standard substitutes (i.e., not including concussion substitutes) to five per team also allowed more players to accumulate game time during the World Cup, further enhancing their development and giving coaches more flexibility to change personnel and tactics earlier in matches.