Practice comes in many forms, and finding the optimal combination is certainly a challenge for anyone working in talent development. In this Science Explained presentation, Dr Paul Ford examines how the best players actually hone their skills on their way to the top, and how coaches can apply the science of practice to get the best out of their squads. The session is followed by a Q&A, hosted by FIFA’s Professor Paul Bradley.

Introduce the three categories of developmental and practice activities. Investigate how elite players balance these activities on the way up the pyramid. Consider how the theory of deliberate practice might be applied to football.

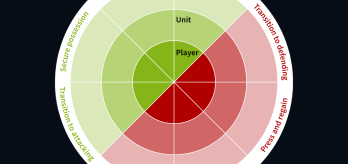

The balance of the different types of practice shifts as players progress up the pyramid, with coach-led practice playing a progressively bigger role. However, the benefits of peer-led play in particular should not be underestimated, particularly in childhood.

Clubs and associations could consider investing in facilities for peer-led play as a way of developing more players. Coaches can experiment with different ways of applying the theory of deliberate practice in training – including when working with their entire squads.

Watch presentation

Read summary

Part 1: The three types of football activity

Alongside matches, previous research into talent development in sport has identified two main types of football activities: peer-led play and coach-led practice. The former is informal and focuses on fun, whereas the latter takes a structured approach to improving performance. There is evidence that the balance between these types changes as players progress up the pyramid, with coach-led practice gradually becoming more common than peer-led play. Significantly, however, there is evidence to suggest that future internationals engage in more peer-led play as youngsters than other players.

Part 2: The benefits of peer-led play

Nybakken and Falco suggested that peer-led play might bring significant advantages over coach-led practice for children, including giving them more games, more time on the ball and more shooting practice. Their hypothesis is arguably strengthened by the existence of “talent hotspots” like south London and the Paris banlieues. Both environments feature plenty of accessible facilities for informal play, and produce a disproportionate number of professional footballers. Clubs and associations could consider taking a similar approach, perhaps by subsidising public pitches in urban areas to get more children playing the game informally.

Part 3: Female players, adolescence and specialisation

Research on the effect of developmental activities on female players is contradictory; three previous studies have reached different conclusions on the types and amounts of activities top players engaged in as children, probably due to between-country differences. However, Horning et al. found that both male and female players engaged in ever-increasing amounts of coach-led practice in adolescence and began to specialise in the sport. Male players who went on to play at international level spent a bit more time than their peers playing sports other than football in a formal setting.

Part 4: The theory of practice applied to footballers

The power law of practice states that early experience of a skill brings rapid improvement, and that progress slows once learners become competent. However, as the late Professor Anders Ericsson observed, experts are not satisfied with competence and tailor their practice to become masters of their craft. Elite footballers are experts, and coaches can use individual performance plans and bespoke, deliberate practice to hone their abilities to extremely high levels. However, this practice needs to reflect the complexity of the game. Skills that cannot be applied during matches are of limited usefulness.

Part 5: Team practice and match play

Finally, Dr Ford considers a fundamental problem with the theory of deliberate practice: it is built on the idea of individual progress. In a football context, this means that neither team training nor match play qualify as deliberate practice. On that basis, Professor Ericsson actually argued that the theory could not be applied to team environments, but Dr Ford challenges this view. To conclude the session, he suggests ways in which coaches might incorporate the principles of deliberate practice into team training sessions by designing exercises around both individual and team tactical objectives.

Q&A

00:33

What are the main shortcomings and limitations of the research and the theoretical content you discussed in your presentation?

03:30

What are the other factors that influence skill development and whether a young player will progress to the professional ranks?

05:07

You mentioned the variability in the data, especially regarding the activities of female players. What does that variation mean in practical terms?

07:18

You alluded to the importance of play in the development of young players. How might we increase the amount of peer-led play young players engage in?

09:05

You mentioned deliberate practice. How might we increase the amount of deliberate practice players are getting?

10:10

Papers tend to focus on quantity of practice. How beneficial might it be to measure the quality of that practice?

12:07

As someone who works full-time in football, I am seeing more specialists and super-specialists entering the football industry. Can you explain why organisations in football should consider employing a skills acquisition specialist, and discuss some of the barriers to doing so?

14:48

I’d like to ask about windows of opportunity. Are there specific windows of opportunity or target age groups for specific activities?

18:00

What are the key messages you’d like practitioners to take away from your session?

Bibliography

Ericsson KA. Towards a science of the acquisition of expert performance in sports: Clarifying the differences between deliberate practice and other types of practice. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2020, 38, 159–176.

Ford PR, Hodges NJ, Broadbent D, O’Connor D, Scott D, Datson N, Andersson HA, & Williams AM. The developmental and professional activities of female international soccer players from five high-performing nations. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2020, 38, 1432–1440.

Güllich, A. “Macro-structure” of developmental participation histories and “micro- structure” of practice of German female world-class and national-class football players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2019, 37, 1347–1355.

Hendry D, Williams AM, Ford PR & Hodges NJ. Developmental activities and perceptions of challenge for national and varsity women soccer players in Canada. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 2019, 43, 210–218.

Hornig M, Aust F & Güllich, A. Practice and play in the development of German top-level professional football players. European Journal of Sport Science, 2016, 16: 96–105.

Nybakken T. & Falco C. Activity level and nature of practice and play in children’s football. International Journal of Environmental Research: Public Health, 2022, 19, 4598.

Platvoet SWJ, van Heuveln G, van Dijk J, Stevens T & de Niet M. An early start at a professional soccer academy is no prerequisite for world cup soccer participation. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2023, 5, 1283003.